The Short Read

If we want sports to go on during a raging global pandemic, we should not simply advocate for sports while ignoring the harms they entail. We need to come to terms with the unjust decisions that have led to the cancellation of sports, and pay attention to the social implications of these decisions outside sport as well. If we want sports, and if we want the athletes competing in them to be healthy, we need to actually do something about improving social conditions.

The Long Read

The Omicron variant is driving a drastic increase in COVID-19 cases, leading to more deaths (in fact hospitalization numbers are the highest they have been) and provincial governments re-introducing more public health measures. The result is that post-secondary athletes are, unfortunately, staring down the high probability of a second consecutive lost season. People are understandably frustrated –after nearly two years of living with this virus one would think we would implement some of the effective public health practices at our disposal.

The main source of uproar I have witnessed among student-athletes stems from the adjusted Ontario restrictions allowing exceptions for “athletes training for the Olympics and Paralympics and select professional and elite amateur sport leagues.” This excludes post-secondary sport associations such as the OUA (Ontario University Athletics) and OCAA (Ontario Colleges Athletic Association). Athletes competing in the OUA and OCAA are certainly “elite”, but we can still participate in the chain of infection and community spread that sends people to hospitals. If we consider the health of the communities that host us as more important than having Doug Ford call us “elite”, then we should be angry that after two years our government has left us without the safety measures to train. There is no doubt that, in our current reality, organized sport taking place indoors would add to the detrimental impact this current wave of COVID-19 is having on our society. It pains me that the overwhelming response of many university athletics departments as well as the OUA has been to complain about the exclusion of their athletes from the “elite” category and ignore the real-world negative impact of including their athletes in the “elite” category.

I think it would be useful to cover some of the driving factors that created this predicament; we need to know what has to be fixed before we can work towards ensuring a safe environment where sport can be played without exposing athletes, coaches, therapists, and their associated communities to a potentially life-altering sickness. But first, it is worth talking about some of the common myths that are used as reasons to pursue a policy of what some might call eugenics.

1. Dispelling Some Myths

What about mental health?

The short version: in no way does letting the virus run rampant through society improve mental health.

There is no doubt that lockdowns can impact mental health, especially when most provinces have taken the “no-fun-all-work” lockdown approach which encourages people to shut down their social lives in favour of risking their lives contracting a harmful virus at work and/or school. I think the detriment to mental health in this case is less about the lockdowns themselves and more about the contradictory nature of them. I cannot imagine anyone’s mental health would improve by watching friends and family members getting sick, suffering long-term effects, or dying because we adopted a policy of no restrictions. I also cannot imagine our social lives would improve in this scenario unless we decided to ignore the virus altogether instead of consistently weighing the risks of placing ourselves in certain situations. A no-restrictions policy is definitely detrimental to the mental health of health care workers and teachers, who are currently short-staffed from burn-out and getting sick. Ironically, the redirection of health-care resources to deal with the massive influx of COVID-19 infections reduces our ability as a society to deal with the mental health issues that already existed before the pandemic. There is even a natural experiment that discusses the impact differing public health approaches were observed to have on mental health: in the first wave of COVID-19, Sweden notably took minimal measures to restrict social activities that spread the virus, yet their mental health suffered comparably to Italy and China, who both enacted lockdowns. Sweden’s death rate, however, vastly exceeded their neighbouring Finland, so the trade-off here is vastly more deaths and similarly poor mental health. To top it off, depression is also a common symptom of those experiencing post-COVID infection symptoms or “long COVID.”

We can do sports safely without harming the community:

To answer this, one simply needs to look at the outbreaks in professional leagues that have substantially more resources at their disposal than Canadian University and College sports associations. As another example, the men’s World Junior Hockey Championship was recently cancelled because of cross infection between the athletes and the hosting community. The only way for sports to be done safely is to get community case counts down first.

Omicron is not very harmful:

Even if it is less harmful than previous variants of COVID-19, Omicron is definitely more transmissible. Unless it is severely less harmful than previous variants, which is not the case, the greater number of people getting infected will still lead to more sickness and death (for example: a virus that kills 1% of 100 people means one death, but a virus that kills 0.1% of 10,000 people means 10). This is why we are seeing record numbers of hospitalizations. Also, the fact that many people getting sick with Omicron are vaccinated, and so have some immune protection, understates the true severity of the variant. We seem to have forgotten that the delta variant still exists, and that letting infections soar only leads to new variants that have no guarantee of being more friendly (recall that delta was worse than the original strain). It’s also well documented at this point that getting infected with COVID-19 is not a “one-and-done” type deal. Vaccines are also unavailable to young children, who are increasingly entering hospitals due to Omicron. Although the effects of long covid are still being documented (including recent data on increased diabetes rates among infected children), they prompt the question: are we sacrificing the next generation of athletes (and humans, more importantly) because we would rather compete than let them?

The economy!

The only economic losses one would expect to see from actually trying to contain the virus are short-term profits. The economy does not run very well if people are too sick to work (and indeed we are seeing worker shortages). It’s also economically detrimental to account for thousands of new people who will need long-term disability support from post-COVID infection when we can prevent those infections in the first place. I guess this problem is nefariously sidestepped by refusing to supply enough PCR tests so that people will be unable to provide evidence for long-term disability claims. From a micro-economic perspective, athletics department staff would suffer losses as their hours of work would be greatly reduced due to the absence of student-athletes. This is a good opportunity to recruit athletics department staff in the fight to ensure a safe environment to play sports.

Omicron is too difficult to contain:

For some reason “living with the virus” came to mean dealing with mass infection in countless waves instead of the way we have lived with other viruses for decades –using a combination of vaccinations, testing, tracing, localized isolation protocols, and other preventative measures. It’s worth noting that measles is an incredibly transmissible virus, but we are able to contain it. As well, communities that took an effective “test, trace, isolate” approach spent less time under “lockdowns” and enjoyed more freedom than those that have not. We only need to look within our own country for an example: limiting COVID-19 case counts to near-zero meant Atlantic Canada was able to run organized sports throughout the fall and winter of 2020-2021, whereas Ontario was largely restricted. We will enjoy more individual freedom if our collective freedom is taken care of first. We don’t even have enough health-care capacity to perform important non-COVID related procedures for people right now. We also don’t have enough ambulances to respond in life-threatening emergencies, which occur frequently enough at sporting events that this should be a concern. Doesn’t seem like freedom to me.

2. How Did We Get Here?

The simple response to a pandemic is to increase funding for health care and preventative measures (namely testing and tracing) to complement a policy of strict, localized lockdowns in an effort to CONTAIN outbreaks. We ended up with health care cuts and large-scale, patchwork “lockdowns” where people are still forced to go to work/school, a policy that CAUSES outbreaks. That sounds backwards!

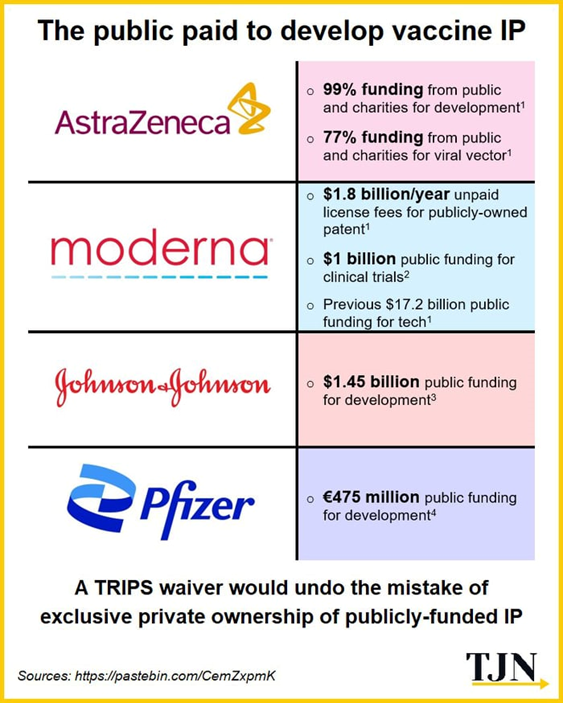

If we look at the way we deal with other crises –whether it’s climate change, houselessness, drug addiction, etc. –a reoccurring theme is that the policy choices often favour the wealthy. The most glaring example of this, on top of continuing to force workers to risk contracting a life-altering sickness, is how governments continue to refuse to waive patent laws that would allow poorer countries to produce the (taxpayer-funded) vaccine. Instead the rich countries are forcing the poor ones to purchase highly priced doses from pharmaceutical companies (or develop their own as Cuba has done). The fact that a large proportion of the world remains unvaccinated helps to increase case counts and produce more variants that could evade previously gained immunity.

Although we hope that political parties ultimately answer to the people who vote for them, they largely serve large donors like wealthy individuals and corporations. In our society, those wealthy individuals and corporations are supposed to try and maximize their profits, not care about the well-being of people. It does not help that in Canada, aside from the CBC, most mainstream news outlets are owned by those same wealthy individuals and corporations. We have embraced an ideology where public services that ensure the necessary means to make a living must be defunded in favour of an unaccountable private sector that only the rich can afford. This prevents numerous individuals from competing in sport because they are denied the means to do so, which reduces the quality of competition and makes OUA and OCAA leagues less elite than they could be.

3. What Can We Do?

Luckily, although politicians are largely dependent on the richest people, their jobs also depend on public opinion. When you don’t have the money, it just takes more work to force politicians to act. People had to fight extremely hard win things like the 40-hour work week and public health care. In 2012, Quebec students successfully kept tuition costs down by launching mass strikes.

One of the main advocates voicing the opinion that the OUA and OCAA should continue (while ignoring the effects of the pandemic) is the so called “Canadian Student-Athlete Association,” which has written in their constitution that “Members have no voting rights on any issues relating to the Association, its organization, structure or governance.” We can do better than that.

If we want to compete without getting ourselves and community members sick, we have to address the undemocratic structures that are preventing us from doing so. This means building a society that embraces democracy politically, but also in our institutions –schools, workplaces, etc. It means building a society that takes care of everyone’s basic needs first and does not put the primary focus on profits. I think once we do that, we should find that sports will come easy

4. The Call

If you find yourself agreeing to what was written and find yourself wanting to take action, we are inviting people to join the grassroots movement, Kilometres for Public Healthcare, which you can do by filling out this form. We saw OUA athletes and alumni come together last fall and put public pressure on the University of Guelph to initiate a third-party investigation into the culture of abuse that it allowed to exist on its cross country and track and field teams. We can do that and more. Although some seem content to ignore these issues, we should not.

In solidarity,

Not Trackie and team